By Paul de Pontbriand Vieira

One of my earliest childhood memories is arguing with my brother and cousins to be the one allowed to ride a faded old red kid’s car with metal pedals that use to hang around my grandfather’s backyard in the 80’s. Back in the days, yeah, I was just like any other kid craving that rush we would get by doing dangerous things like climbing on trees and riding environmentally friendly fast “cars” in any small paved area we could find (even though I had no idea what that was or what it represented). At one point during those early years that car became too small and not as fun as owning my own bike.

One of my earliest childhood memories is arguing with my brother and cousins to be the one allowed to ride a faded old red kid’s car with metal pedals that use to hang around my grandfather’s backyard in the 80’s. Back in the days, yeah, I was just like any other kid craving that rush we would get by doing dangerous things like climbing on trees and riding environmentally friendly fast “cars” in any small paved area we could find (even though I had no idea what that was or what it represented). At one point during those early years that car became too small and not as fun as owning my own bike.

Times were changing. And in fact they did. From a safe community where in the old days I would feel comfortable leaving my bike thrown on the ground in front of a neighbor’s front gate – just three blocks away from my house – while playing ball in his backyard (or Atari on a 13 inch TV), I was suddenly facing my parent’s anger and disappointed look for having my brother’s bike stolen in the few seconds I had left it unattended outside of my favorite video rental store. To make things worse, just a few months earlier the first adult sized mountain bike I owned had also been stolen. I lost the courage to ride or own another bike again (to be honest, I was also afraid of being bitten a second time by my other neighbor’s crazy old German Sheppard that use to think my leg, while riding my bike, was his own chewing bone).

While spending years suffering from that guilt I found pleasure walking and, when dealing with great distances – usually to my high school – the use of public transportation. At this point you might be asking yourself – Now, why is he telling me all this? Well, that’s because up until now I had no idea I was unconsciously making use of problem solving techniques that would help me overcome particular challenges.

In “Thinking in Systems”, by Donella Meadows, we are introduced to problem solving on different scales through the methodology of ‘system analysis’. From concepts such as “reinforcing feedback loops” to “stabilizing loops”, she shows how to develop systems-thinking skills and how to apply them in a broad variety of situations.

Our current society is facing great threats as it keeps exploring systems that are bound to fail. The challenge, according to Meadows, is being able to understand that these problems cannot be “solved by fixing one piece in isolation from the others”, as even smallest details can have huge influence and power to “undermine the best efforts of too-narrow thinking.”

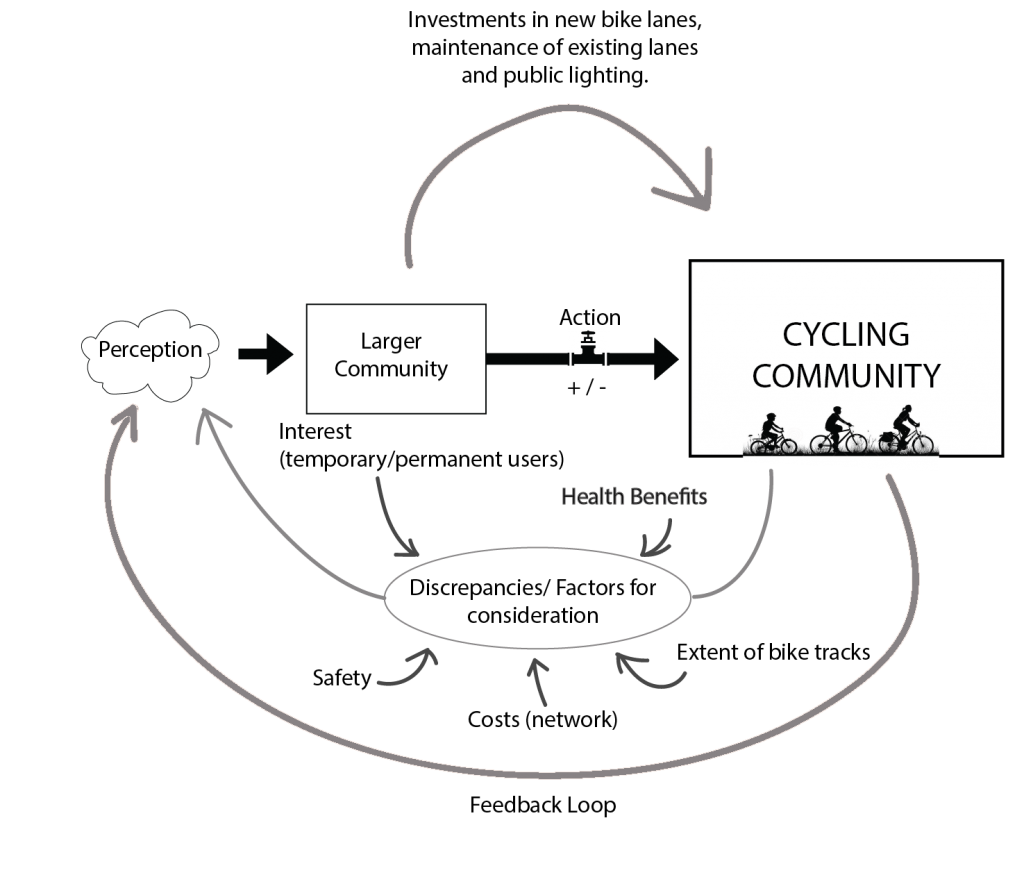

To explore her methodology, one can look at bicycle commuting in Savannah, GA, as a feedback loop. But what is a feedback loop? According to the American Heritage Dictionary of English Language, it is “the section of a control system that allows for feedback and self-correction, and that adjusts its operation according to differences between the actual and the desired or optimal output.” In other words, it is a system that runs on a cycle comprised of decision-making, actions, reactions and some sort of induced internal change.

This diagram introduces the cycling community as the main stock and reaction of a feedback loop. That reaction influences a cloud of perception (noticed reactions) that is linked to the larger community of people (not only cyclists) and is influenced by the actions derived directly from that larger community. These actions, represented by a valve, define the amount of change expected within the cycling community – usually their number, as it is here the main goal.

Cycling Community Feedback Loop. VIEIRA (2016).

Cycling Community Feedback Loop. VIEIRA (2016).

The way it works its rather simple: from a pre-existing group of cyclists, usually permanent (meaning they use their bicycle at least once every day), the general community gets feedback regarding the safety of the roads they use, the condition of bike lanes and the extent of those lanes – appropriate or not. It also brings attention to health benefits from such regular activity, and with such constant use of bicycles comes maintenance and/or used bikes for sale that create a bicycle economy. From that larger community, those in power of change decide how much to actually invest on what could end up being new bike lanes, maintenance of existing ones, public lighting, etc – or lack of it; usually looking at short term benefits. Aside from political actions, we also find measures that motivate a change in cycling education and general traffic behavior (a respect that cyclists expect from drivers when sharing space on roads), as well as a change in their own habits. This is a starting point for cycling community growth.

Behind the dilemma of constant population and, consequently, urban growth vs. sustainable development, we find a somewhat immature cycling system being explored in our cities (when even explored at all) and are reminded to “pay attention to what is important, not just what is quantifiable” as the first step toward finding proactive and efficient results. Dave Horton and David Dansky (2013), in an article on “urban cycling”, agree that cities where walking and cycling are made easier, more enjoyable (and where driving is harder and less pleasant) are places where people wish to live, to spend time, to shop, to interact with other people. A quote from Kevin Lynch’s book “The image of the city” depicts the importance of spatial problem solving in the process of “wayfinding” when designing cities:

“Not only is the city an object which is perceived (and perhaps enjoyed) by millions of people of widely diverse class and character, but it is the product of many builders who are constantly modifying the structure for reasons of their own. While it may be stable in general outlines for some time, it is ever changing in detail. Only partial control can be exercised over its growth and form. There is no final result, only a continuous succession of phases.”

In Europe, cycling has moved up the agenda of town and city planners with a higher frequency in recent years, given its benefits as a healthy, highly sustainable form of transport. Old preconceptions about the importance of cars and roads for fast traffic directly related to economic development are being replaced by a more eco-friendly mindset allowing big changes in the way society works.

Up to this point, a good number of cities with historic downtowns have managed to reduce traffic or even make a car free zone, allowing safer bike lanes to be developed along with walkable areas and connected green spaces. In the Netherlands, 27 percent of all trips and 25 percent of trips to work are made by bike, with an average distance cycled per person per day of 2.5 km. Amsterdam is one of the most bicycle-friendly cities in the world with more than 400 km of bike lanes. In the city of Krommenie, Holland, a solar path was recently inaugurated and has been generating a growing positive response from their cycling community. It has been said that the Dutch solar bike path is generating more electricity than originally planned, which is excellent news as it can make this pioneering innovation in the field of energy harvesting to be copied in other cities. These are all strategies that prove to have a positive impact not only in people’s health and well being but overall economy profitability as well.

In 2013, the city of Savannah, GA, achieved designation as a Bicycle Friendly Community, but according to John Bennett, in his article Bicycle Friendly, Officially, there is still an absence of a comprehensive bicycle infrastructure network, and the presence of drivers who “may not yet be aware that they need to share the road with cyclists” still make up for a good share on the general insecurity felt on the streets.

The Savannah College of Art and Design (SCAD) plays a major role in today’s cyclist community with a large number of students opting for a bike as their primary means of transportation – usually from home to campus and vice-versa. At the moment, the most common excuses given by students who don’t own a bicycle are the lack of public lighting for their night time ride back from campus (making a few of the ones that do possess a bike to use the bus on the way back), the lack of safety in particular communities, and a disrespect from drivers when sharing street space with cyclists.

The following is a summary of the basic strategies that could help grow Savannah’s cyclist community as well as allowing the city to achieve a true status of sustainable city and cyclist friendly:

- Develop the city’s infrastructure by creating more bike-share stations

- Create a full network of bike lanes and pedestrian walkways throughout the historic downtown.

- Dramatically reducing car access on specific streets to property owners (residential and commercial) only.

- Identify separate individual central bike lanes with public lighting reinforced by solar paths.

Savannah is privileged to have an amazing urban grid that allows a relatively easy flow of cars in and out of its downtown area. A few streets already share space with bike lanes but the overall feeling is of insecurity. By taking advantage of the short distance between parallel streets, it shouldn’t be hard to simply limit access while connecting to squares and parks. A public pathway would be available for locals and tourists to wander around and help improve safety conditions for both walking users and cyclists.

Savannah and other similar cities have tremendous potential for a vibrant bike community if biking is treated as system of many parts. Understanding that system as a reinforcing feedback loop, whether contracting or growing, is the key to thoughtful urban design and effective alternative transportation planning within an interconnected community of cultural influences.

Paul de Pontbriand Vieira is a SCAD Architecture student from Brazil.