by Alexis X.A. Roberts

“I think that a strong sense of identity is like an ideology: You anchor something, when you’re feeling slightly at sea, by coming back to that place.” – Penny Martin

“I think that a strong sense of identity is like an ideology: You anchor something, when you’re feeling slightly at sea, by coming back to that place.” – Penny Martin

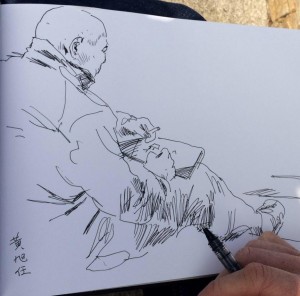

8,212 miles away from his homeland of Taiwan, Hsu-Jen Huang has chosen Savannah, Georgia as his anchor, but those who know him understand that he remains on the go. The words on this screen aren’t the only evidence, for Hsu-Jen has the passport stamps, photographs and FB posts to prove it. Beyond his love of architecture and photography, the ever smiling but seriously gifted guru is able to hang with the best of urban storytellers. A Thousand Miles is his visual curation of landmarks from his wanderings.

Stories bring meaning into our lives. They indicate how and why we understand ourselves in the manner that we do. It matters not whether these tales are scripted, drawn or spoken in nature, the true significance is found when we pass them on. In light of this, it stands to reason that we constantly add to and share our stories with others. Fastened to the walls of Eichberg Hall’s second floor hallway are fragments of such stories. They are pieces of Hsu-Jen’s history. Many of us seek to make the world a more beautiful place but few of us actually stop to record the beauty that already exists within it. Makers like Hsu-Jen, however, though in motion, often take time to document both natural and urban worlds.

Stories bring meaning into our lives. They indicate how and why we understand ourselves in the manner that we do. It matters not whether these tales are scripted, drawn or spoken in nature, the true significance is found when we pass them on. In light of this, it stands to reason that we constantly add to and share our stories with others. Fastened to the walls of Eichberg Hall’s second floor hallway are fragments of such stories. They are pieces of Hsu-Jen’s history. Many of us seek to make the world a more beautiful place but few of us actually stop to record the beauty that already exists within it. Makers like Hsu-Jen, however, though in motion, often take time to document both natural and urban worlds.

Perhaps he is a true nomad. During studio hours you’d have better luck finding Hsu-Jen wandering between studios dropping small gems of knowledge than inside the partitioned walls of his own studio space. For those more familiar with his role as professor of architecture, it may be surprising to learn that it is outside the walls of the institution that he is most creative. The wanderer’s path is his true makerspace. It is a studio in nonstop transformation. Ever-changing cityscapes provide the perfect backdrops and focal points for his work. Despite a seemingly essentialist approach, his sketches continue to move and inspire both students and colleagues alike. Although they may feature intentional markings, Hsu-Jen’s work never lacks personality or feeling; an accurate reflection of the man behind the brush and pen.

For the most creative individuals among us- meaning those who’ve discovered and developed their craft- life must remain an adventure; almost decidedly so. Growth in an ingenious field requires quite a bit of exploration, spontaneity and in some cases bravery. The same rings loud and true for Hsu-Jen. Anyone who has taken Hybrid Media or has been on the Hong Kong Immersion Trip with Hsu-Jen can attest to that. Working under Hsu-Jen is a collaborative experience that stresses the importance of seeking new techniques and experimental modes of visual communication. This is how we expand and thus refine our toolkit; how we gauge who we are. The result of such exploration is evidenced in A Thousand Miles.

“Sometimes the ones who have sight are the blindest.” R. Fenty

Many moments are featured here and countless others line Hsu-Jen’s sketchbooks. However, he shows few signs of slowing his travels or artistic output. In an increasingly technological field governed by deadlines, there are those who argue against the significance of this art form. The sheer craftsmanship and skill needed for such work is not the only justification for graphic recording, but it should serve to remind us to look up. It is never too early to see the world around us. We may all view it from our own perspectives but, we can express this through a common language if we choose to do so. Having the ability to see cannot not rival the gift of sight beyond the surface, but pausing to sketch forces us to engage our senses. It allows us to introduce ourselves to local and foreign characters; to interpret living environments at work. Some creatives search their memories and souls to reflect the happenings of their past but this immediate confrontation changes one’s output and perspective in a contrasting way.

Nature is a life-changing concept. Learning places and more importantly people, is something different altogether. Artists of the urban landscape give insight into the worlds and systems they capture; making for some incredible ethnographic offerings. A Thousand Miles is a visual journal but conversations with the artist reveal it to be something far greater than a collection of building perspectives and hours of mark making. Hsu-Jen sketches to check in with his extra-sensory self. Our resident urban explorer doesn’t simply hop from region to region. By truly immersing himself within new surroundings, he experiences the raw nature of place. There are layers of complexity to the built world and those who remain solely transient don’t allow themselves to consider the work before and around them. If you take one thing away with you after viewing Miles, let it be the admonition to pause, look, listen, smell and when appropriate, touch. This exhibition and conversations around it indicate that some of us are paying attention.

We have all heard the arguments over the death of hand work within the current world of architecture. Has it lost its value in favour of the modern machine? Will the young be given the opportunity to appreciate it? What of the relationship between artist and his toolkit; mankind and his built works? Sketching as a way of seeing has shifted over time but, its ability to inspire remains constant. There are many reasons to believe that its prominence will return. Many of us continue our personal search for the meaning in our lives. Life is indeed a process; the journey we take to do great things, to settle down and eventually to die. For the creative, this journey is one of continued change. Never complete or officially mastered, each experience darkens or lightens the overall image. What stories will we leave behind?

Pinned to these walls are captured moments, pieces of time and parts of Hsu-Jen’s own personal journey; parts of him but apart from him. Unafraid of a little grit or colour, each stroke emits a wild but somehow experienced measure. They possess a certain structure yet own their ghostlike rhythm. Though confined to the surface of the canvas, it seems this is where Hsu-Jen is most free. This is work for the seeing, nomadic folk but, also for those who aspire to be.

Alexis X.A. Roberts is a currently pursuing his M.F.A in Design for Sustainability at SCAD and recently graduated with his M.Arch in 2015 from SCAD’s School of Architecture.