by Elaine Gallagher Adams, AIA, LEED AP

SCAD hosts more than 250 students annually to study les beaux arts in Lacoste, France,  a town that in any other context would be considered a world class slowcation destination. This is a place that, upon arrival, calms the heartrate and demands your undistracted appreciative attention. As students wake and emerge from their hobbit holes the first morning, whispered declarations of “I can’t believe I’m in this place,” are sent out to the frosty valley below as they stand in wonder pausing on a 400-year old stone terrace.

a town that in any other context would be considered a world class slowcation destination. This is a place that, upon arrival, calms the heartrate and demands your undistracted appreciative attention. As students wake and emerge from their hobbit holes the first morning, whispered declarations of “I can’t believe I’m in this place,” are sent out to the frosty valley below as they stand in wonder pausing on a 400-year old stone terrace.

Students are here to study though. It is a regular quarter term here in Lacoste, uninterrupted by hurricanes and green beer holidays. They attend class and do real work, take tests, and go on magnificent field trips to Roman ruins, textile studios, cemeteries, edgy art exhibits, Impressionist landscapes, and world class contemporary architecture. We spend one fantastic week in Paris visiting famous museums and lesser known gems. My architecture students thoroughly enjoyed the Louis Vuitton Foundation designed by Frank Gehry, which included a beautifully curated traveling exhibit from MOMA. Some class groups visited the Musée de la Chasse et de la Nature (Museum of Hunting and Nature – Taxidermy) and the Musée des Arts et Métiers (Museum of Arts and Trades), learning that sometimes our very best experiences are the unexpected finds. A spontaneous invitation to tour L’Ecole des Beaux Arts studios left our students both envious of those Parisian students and comparing SCAD’s own similar resources, as well as appreciative of our advanced technologies at SCAD.

We are fattened up by three French chefs in the school kitchen, spoiling us silly with tartes, coq-au-vin, eclairs, religieuse pastries, ratatouille, and legumes that make me long to experiment in my own kitchen. Yes, we walk ten thousand steps every day, climbing the equivalent of 53 stories, and we need those calories! Don’t expect to lose weight, but you will indeed get fit. Don’t bring dress shoes. You’re on a mountain, navigating Roman roads and quarries.

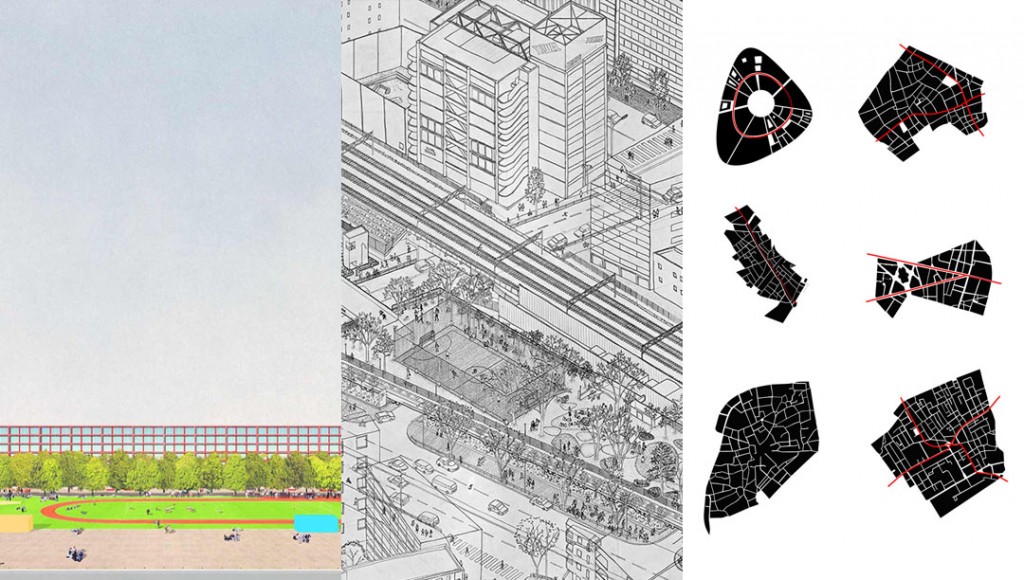

Lacoste offers SCAD students an extraordinary experience. Housed in 12th century buildings filled with creative people from varying programs, our architecture students are embracing game design, preservation design students are diving into print-making, and painting students are basking in European history. As a professor of architecture, this is one of the richest teaching environments I can imagine. The quarter comes to a poetic ending with Open Studio, a multi-gallery exhibit of students work, much of it for sale. You will see examples of animated films, ceramics, textile art, sketchbooks, painting, sculpting, architecture, print-making, and more. Hundreds of visitors regularly attend this event in this remote village, validating the high quality of the work created by SCAD students.

Lacoste offers SCAD students an extraordinary experience. Housed in 12th century buildings filled with creative people from varying programs, our architecture students are embracing game design, preservation design students are diving into print-making, and painting students are basking in European history. As a professor of architecture, this is one of the richest teaching environments I can imagine. The quarter comes to a poetic ending with Open Studio, a multi-gallery exhibit of students work, much of it for sale. You will see examples of animated films, ceramics, textile art, sketchbooks, painting, sculpting, architecture, print-making, and more. Hundreds of visitors regularly attend this event in this remote village, validating the high quality of the work created by SCAD students.

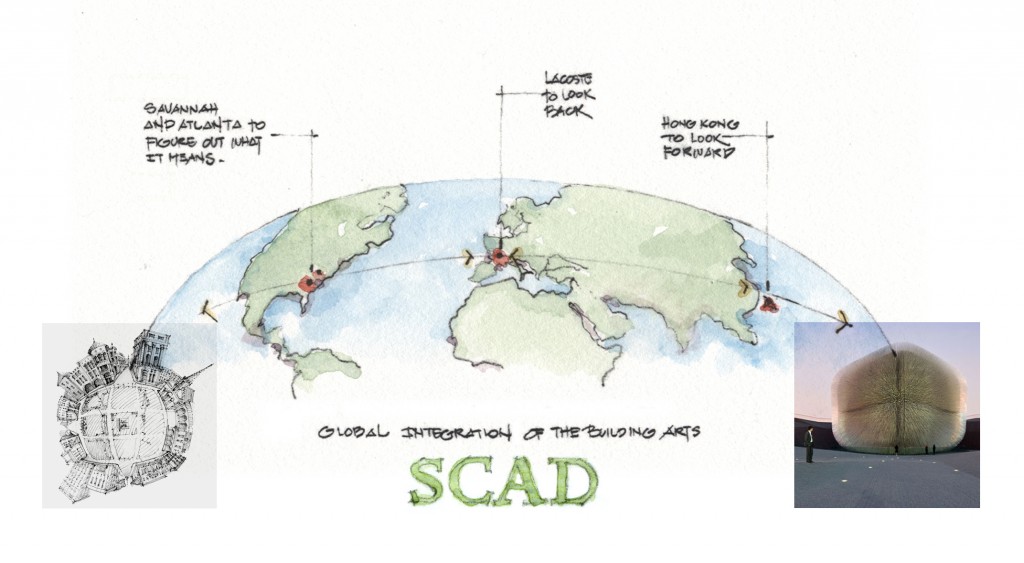

SCAD offers classes in five locations: Savannah, GA; Atlanta, GA; Lacoste, FR; Hong Kong, CH; and our newest campus Online. Tuition and fees remain the same for all locations, making seamless transitions from campus to campus. This means ALL students have access to these life-changing experiences, many traveling internationally for the first time. So come with us next year! You’ll never forget it.

Elaine Gallagher Adams, AIA, LEED AP BD+C, is a professor of architecture, urban design, preservation design, and sustainable design at SCAD [www.scad.edu], currently teaching in Lacoste, France.