I have spent the past three years of my life studying architecture. Three years of pretending that “I’m definitely not going to need to pull an all-nighter tonight.” Three years of gluing tiny paper columns to tiny paper buildings, clicking through Archdaily articles, and wondering how many imaginary people should realistically be hanging out in imaginary gathering spaces. Three years of hard work, hard study, and wait-I-forgot-my-physical models, and I am not going to be an Architect.

That’s right, I will be getting my undergraduate degree in architecture and, unless something drastic happens, am not going to be an architect… or an interior designer, an urban planner, or a sustainability consultant. During the long schooling process, I made the very important discovery that I am not interested in pursuing a career in this field. The building arts field just doesn’t light my fire, and it hasn’t from the start. And that’s okay, I desperately tell myself as I hear students anxiously comparing internship applications and grad school plans. It’s okay if at any point, now or in the future, you find that you are straying from the path of the building arts, because you’ve collected some pretty valuable tools along the way. An architecture education provides much deeper skills than just designing and presenting buildings.

“Less is more,” is one of the first architectural concepts taught in Intro to Architecture, and is one of the furthest reaching. The phrase has grown so well known that it precedes even the person who uttered it. Recognizing the value of minimalism allows us to design buildings that are more practical, economical, and (at least right now) more stylish. Beyond design, the concept of minimalism can be applied to how we work, by teaching us to put more effort into fewer concepts. It is the idea of quality over quantity, which is easily translatable to a variety of fields of work. It is also a lesson in how to live our lives. Fewer distractions mean greater speed, concentration, and quality of work. Fewer, more significant possessions means less room needed to store them, less money going to corporate giants, less items filling landfills in the future, and greater appreciation of what possessions remain. Minimalism stems from design and feeds into allowing us to be better, faster, and happier contributors to the world.

“We do not design in a vacuum” has been constantly reiterated throughout my architectural education. I have learned through the process of designing buildings and spaces that there are forces beyond myself that effect me and that I am in turn affecting. Not only do we need to be aware of ways that we can manipulate design to serve a purpose of whatever kind, but we learn to be aware of our unintended consequences on the world through design, art, and action. We need to be aware that our courtyard designs could discourage crime, strengthen a community and get people to stop and smell the roses, but they can also direct polluted water to the ocean, encourage social stratifications, or eliminate an animal’s habitat. This lesson stretches beyond architectural design to our everyday lives, we find that everything we do has an immediate and not-so-immediate effect on other people, other animals, and becomes a part of history. Architectural design has taught me to educate myself on my effect on the world so that I can strive for as positive an impact as possible.

“Nothing you do should be arbitrary,” is told to architecture students constantly through their schooling. Their instructors are repeatedly asking “Why?” Why is your building shaped that way? Why is it facing that way? Why did you choose that material? If the answer is “I don’t know,” or “I didn’t really think about it,” then you’ve done yourself and your design a disservice. Every choice made in architecture is a very expensive, and potentially dangerous, choice. So building arts students are pushed to consider every facet of their designs and to be able to manipulate those facets to create a comprehensive whole. Even outside of the field, the ability to objectively question your choices and analyze their impact on the whole work is indispensible. It’s what makes great works of literature so successful; every detail serves a greater purpose in the story. It’s a skill used in business, painting, songwriting, branding, and editing. If the details are sloppy and inconsistent, the whole does not have the desired effect. Learning to design a successful building is learning to create a relatable overall experience through manipulation of details.

“Do more than just architecture,” does not mean to me to do “architecture with a capital A” or include elements of other building arts fields in my design work. Doing more than just architecture means that all art forms are linked. It means that architecture becomes a space to highlight the sound of music, to make a painting shine, or to frame a dancer’s gliding pirouette. It means that powerful films like Metropolis look to monumentality in architecture as a means of representing the social striations of the imagined future. It means that Frank Lloyd Wright did not just design homes and office buildings but also chairs, door knobs, and patterns. To study architecture is to learn a multi-purpose design process that can apply to any creative field, art or otherwise.

I majored in architecture, and now I can feel my life drifting down a different path. But I’m not a failure, and I haven’t wasted four years. Yes, I was obviously taught very building arts specific skills and knowledge, like how HVAC systems work, the nominal and actual sizes of lumber, and which way egress doors should definitely not be drawn (swinging in.) Maybe this information will be useful outside of the field, or maybe not. But an architectural education also teaches more unique skills than just general art and design, although I have learned InDesign, hand sketching, and the value of craftsmanship. More general than just buildings, more specific than just art, getting a degree in Architecture has provided me with a unique understanding of the world around me and how I affect it. So don’t be disappointed or afraid if you feel yourself desiring to become an entrepreneur, filmmaker, politician, or dog/emu trainer. It’s all a part of the journey.

And you’ll definitely never forget to draw your north arrow.

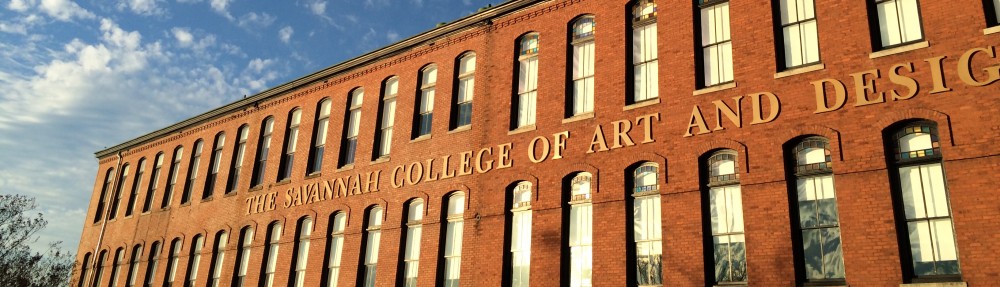

Ragon Dickard is a terrific Senior at the SCAD School of Architecture. (Architecture lost her, but the world wins her. SCAD says, “You’re welcome, World.”)

By Emad M. Afifi, D. Arch.

By Emad M. Afifi, D. Arch.